Person-Centred Care blogs

Hydrotherapy - the ‘Biologic’ in the Non-Pharmacological Management of Axial Spondyloarthritis?

The Pre-Pandemic Role of HydrotherapyNon-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy are the first line of intervention in the management axSpA (1) with escalation to Biologic therapy a second-line intervention (2) (3). Physiotherapy is recommended to include education and exercise prescription from a specialist physiotherapist (3). Hydrotherapy, now called aquatic physiotherapy, has been integral to the management of AS and axSpA for many years and is recommended as an adjunctive therapy (3). The Current SituationDue to COVID-19, access to aquatic physiotherapy has been limited despite guidance on safe practice since June 2020 from the Aquatic Therapy Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (4). This has left many pools under threat and so an alliance has been formed, led by NASS, with a manifesto published which aims to protect, support and promote aquatic physiotherapy (5). With this in mind now is a good time to consider the evidence for aquatic physiotherapy in axSpA and its potential future role. Is hydrotherapy the ‘biologic’ in the non-pharmacological management of axSpA?   Summary of Published Research EvidenceThere is published research investigating the effect of a range of aquatic interventions on axSpA. Systematic review and meta-analysis has found aquatic physiotherapy can statistically significantly improve pain and disease activity (6) and is an appropriate alternative when land-based exercise is not well tolerated (7). Systematic review of both land and aquatic exercise in AS supports an individualised multimodal approach to exercise prescription (8). This has been further supported by systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of physiotherapy including aquatic physio in axSpA (9) with specific management approaches having different benefits (10).Individual studies have found aquatic physiotherapy improves pain, metrology, (11) disease activity and quality of life in axSpA, with improvement in quality of life statistically significantly greater than compared with land based exercise (12). In addition aquatic physio has been found to improve pain, stiffness, disease activity and function when combined with a stretching programme (13), with improvement in pain, function, metrology and disease activity seen at 6-month follow up when combined with spa therapy (14). Aquatic physiotherapy has been shown to improve pulmonary function in AS (15) with potential additive benefits compared to land based training (16), while Gunay 2018 (17) reported performing balance training in warm water had positive effects on stability compared with land based training. Qualitative research in spondyloarthritis has found aquatic physiotherapy to have a wide range of reported benefits including: energy, sleep, cognitive function, ability to work and participation in daily life (18). Patients also reported that exercising in warm water had an important positive impact on wellbeing while having an experienced instructor had an important role in coaching and reassuring. A national survey of NHS hydrotherapy provision (19) found patients reported similar benefits seen in research trials and a postcode lottery in accessing services due to pool closures. Aquatic physiotherapy is commonly seen as costly and is a target for making savings through hydrotherapy pool closures and gradual disinvestment in facilities, however aquatic physiotherapy has been found to be cost-effective for a range of musculoskeletal disorders (20). Lineker 2000 (21) found that access reduced use of healthcare and reliance on others, while patients have reported reduced use of analgesia and NSAID’s (21) (22). Next stepsTo optimise the role of aquatic physiotherapy in the management of axSpA further quality research with larger sample sizes is required with a focus on the dose, and content of the aquatic exercise programme. There may be differences in response with different groups of patients: for example radiographic and non-radiographic disease or with the level of disease activity. Research investigating these cohorts of patients would be of more value than comparing aquatic physiotherapy versus land based alternatives with a heterogeneous sample. Study cohorts should mirror clinical practice and as such it would be interesting to research the effect of aquatic physio on patients with axSpA who struggle to tolerate land based exercise, have high disease activity or are being considered for escalation to Biologic therapy. As part of a multi-modal approach to holistic care in axSpA it is important to consider qualitative research and other forms of evidence such as service evaluations, case studies and testimonials. This can capture the positive impact on quality of life commonly seen and reported in clinical practice. We need to be better at collecting and sharing different forms of evidence as formal research takes time and money. Led by NASS, the Aquatic Physiotherapy and Hydrotherapy Alliance will play a pivotal role in shaping the future of aquatic physiotherapy in the management of axSpA and other neuromusculoskeletal conditions. As we move forward, aquatic physiotherapy services need supporting voices from within and out with the profession to advocate for this valuable specialty and indeed for our patients. It is vital that we listen to our patients who are the experts in managing their condition as part of a person-centered approach to care. People living with axSpA have long been telling us the benefits of hydrotherapy to their health and well-being. We need to aim for a future where there is equity of service provision and where clinicians through informed and shared decision making are able to prescribe the right rehabilitation at the right time to those most in need. ConclusionCurrent published research evidence supports the prescription of aquatic physiotherapy in axSpA as an adjunctive therapy with potential added benefits to well-being, pulmonary function, use of healthcare resources and of medications. There is also evidence to support aquatic physiotherapy as a second line intervention for those struggling to tolerate land-based exercise. In this sense, aquatic physiotherapy could be considered a non-pharmacological second line intervention in the way that Biologic therapy is used as a second line intervention in the medical management of axSpA. Further quality research and evidence gathering is required to establish which people living with axSpA are likely to benefit most from aquatic physiotherapy. In the meantime, clinicians can exercise clinical reasoning to provide person-centered care and prescribe aquatic physiotherapy for axSpA based on clinical need and individual preferences.

Alasdair

REFERENCES 1. Noureldin, B., & Barkham, N. (2018). The current standard of care and the unmet needs for axial spondyloarthritis. Rheumatology, 57(suppl_6), vi10-vi17.2. Perrotta, F. M., Musto, A., & Lubrano, E. (2019). New insights in physical therapy and rehabilitation in axial spondyloarthritis: a review. Rheumatology and therapy, 6(4), 479-486.3. McAllister, K., Goodson, N., Warburton, L., & Rogers, G. (2017). Spondyloarthritis: diagnosis and management: summary of NICE guidance. Bmj, 356.4. ATACP (2021). ATACP Recommendations for safe aquatic physiotherapy practice in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. ATACP. https://atacp.csp.org.uk/system/files/documents/2021-10/ATACP%20Recommendations%20for%20safe%20aquatic%20physiotherapy%20in%20relation%20to%20COVID-19%20pandemic%20edit%2001.10.21.pdf5. NASS (2021). A National Manifesto for Hydrotherapy. ATACP. https://atacp.csp.org.uk/system/files/documents/2021-09/Hydrotherapy%20Manifesto%20September%202021-1.pdf6. Zhao, Q., Dong, C., Liu, Z., Li, M., Wang, J., Yin, Y., & Wang, R. (2020). The effectiveness of aquatic physical therapy intervention on disease activity and function of ankylosing spondylitis patients: a meta-analysis. Psychology, health & medicine, 25(7), 832-843.7. Liang, Z., Fu, C., Zhang, Q., Xiong, F., Peng, L., Chen, L., ... & Wei, Q. (2021). Effects of water therapy on disease activity, functional capacity, spinal mobility and severity of pain in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(7), 895-902.8. Zão, A., & Cantista, P. (2017). The role of land and aquatic exercise in ankylosing spondylitis: a systematic review. Rheumatology international, 37(12), 1979-1990.9. Gravaldi, L. P., Bonetti, F., Lezzerini, S., & De Maio, F. (2022, January). Effectiveness of Physiotherapy in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. In Healthcare (Vol. 10, No. 1, p. 132). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute.10. Chang, W. D., Tsou, Y. A., & Lee, C. L. (2016). Comparison between specific exercises and physical therapy for managing patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Clinical & Experimental Medicine, 9(9).11. Aydemir, K., Tok, F., Peker, F., Safaz, I., Taskaynatan, M. A., & Ozgul, A. (2010). The effects of balneotherapy on disease activity, functional status, pulmonary function and quality of life in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa, 35(5), 441-446.12. Dundar, U., Solak, O., Toktas, H., Demirdal, U. S., Subasi, V., Kavuncu, V. U. R. A. L., & Evcik, D. (2014). Effect of aquatic exercise on ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology international, 34(11), 1505-1511.13. García, R. F., Sánchez, L. D. C. S., Rodríguez, M. D. M. L., & Granados, G. S. (2015). Effects of an exercise and relaxation aquatic program in patients with spondyloarthritis: a randomized trial. Medicina Clínica (English Edition), 145(9), 380-384.14. Ciprian, L., Lo Nigro, A., Rizzo, M., Gava, A., Ramonda, R., Punzi, L., & Cozzi, F. (2013). The effects of combined spa therapy and rehabilitation on patients with ankylosing spondylitis being treated with TNF inhibitors. Rheumatology international, 33(1), 241-245.15. Ferreira, M., Lopes, A. A., Silva, F., Pereira, S., & Eason, J. (2013). Effect of an aquatic therapy program on pulmonary function in ankylosing spondylitis. The Journal of Aquatic Physical Therapy, 21(1), 2-7.16. Gurpinar, B., Ilcin, N., Savci, S., & Akkoc, N. (2021). Do mobility exercises in different environments have different effects in ankylosing spondylitis?. Acta Reumatologica Portuguesa, 46(4), 297-316.17. Gunay, S. M., Keser, I., & Bicer, Z. T. (2018). The effects of balance and postural stability exercises on spa based rehabilitation programme in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation, 31(2), 337-346.18. Lindqvist, M. H. (2013). Hydrotherapy treatment for patients with psoriatic arthritis—a qualitative study. Open Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 1(02), 22.19. Martin, M., Gilbert, A., & Jeffries, C. (2018). OP0279-HPR A national survey of the utilisation and experience of hydrotherapy in the management of axial spondyloarthritis: the patients’ perspective.20. Teng, M., Zhou, H. J., Lin, L., Lim, P. H., Yeo, D., Goh, S., ... & Lim, B. P. (2019). Cost-effectiveness of hydrotherapy versus land-based therapy in patients with musculoskeletal disorders in Singapore. Journal of Public Health, 41(2), 391-398.21. Lineker, S. C., Badley, E. M., Hawker, G., & Wilkins, A. (1999). Determining Sensitivity to Change in Outcome Measures used to Evaluate Arthritis Community Hydrotherapy Programs. The Arthritis and Immune Disorder Research Centre, the Toronto Hospital.22. Januário, F., Almeida, J., Serra, S., Amaral, C., Machado, P., & Rodrigues, L. A. (2012). Characterization of Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis in Hidrokinesitherapy–A Multidimensional Assessment. Acta medica portuguesa, 25(5), 301-307.

Dementia and AS

The last 14 years of my career has been a balancing act! Whilst developing my skills and knowledge to support my professional career in my role as an advanced practitioner physiotherapist in rheumatology, I have also been a main carer firstly of my mum, who passed away last year, and more recently my dad too. This role has been personally the very most challenging of my life, learning about Alzheimer’s and dementia, the social care system in its’ intricacies and the various gradual changes which inevitably occur over the course of the condition and how to navigate them together. Through this time I have sadly observed a number of my patients within my axial spondylarthritis clinics who themselves have developed cognitive decline and dementia. It sparked my thinking about the link between inflammatory diseases and dementia and the challenges those living with these conditions and their families, friends and carers face and we clinicians can face trying to ‘get it right’ for all. It can seem like an impossible battle. My blog this month is not designed to give a comprehensive review of all evidence nor a list of does and don’ts but simply a prompt to consider things perhaps a little differently if you are in the privileged (but challenging) position to be caring or clinically involved with a patient who also suffers with cognitive decline or dementia. According to latest figures from the Alzheimer’s Society, there are approximately 900 000 people diagnosed with dementia in the UK, with 1 in 20 of these being under the age of 65. The most common form is Alzheimer’s disease, though other forms of dementia exist (frontal-temporal, vascular, dementia with Lewy bodies). The key features in the early to middle phases can include memory loss, difficulty with speech and word finding, difficulty with task completion, concentration, decision making, coordination and balance. It is often associated with histories of anxiety and depression or psychological trauma (Ownby et al. 2006), cardio-vascular disease (Newman et al. 2006), smoking or physical inactivity, all of which are associated with increased risk of inflammatory joint diseases, including axial spondyloarthritis. There is some thought that the links between the inflammatory processes in rheumatic diseases and cardiovascular conditions and those linked with dementia may be related to biological processes which may contribute to amyloid plaques developing within the brain and the subsequent brain changes associated with dementia symptoms. Jang et al. (2019), conducted a population study which looked at population data from the Korean National Health Insurance System. Using various statistical analysis, they identified there was an increased prevalence of overall dementia in populations of people living with axial spondylarthritis. So, with this in mind, we are likely to encounter more people in time with a combination of these conditions, it is important we think about how can we help advise our patients to reduced their risks. This generally includes much of what we should already be doing (NICE 2016) such as comprehensive lifestyle advice, smoking cessation, increasing physical activity, anxiety management and psychological health improvements. Other aspects of course may need to be considered also, for example: how do you perform a BASDAI on somebody who doesn’t understand the questions fully to answer them, but is on a biologic? There are a number of studies which have looked at pain assessment in musculoskeletal disorders and in the elderly with cognitive impairment though many lack robust methodology and this as such lessens their reliability (Lichtner et al 2014). From discussions with my Trust’s Dementia Matron and reviewing of the British Pain Society Guidelines in 2007, there is a suggestion to use a Pain Thermometer in early and moderate level cognitive impairment and the Abbey Pain Score system in moderate to severe impairment. Neither of these are particularly well validated and certainly not so for assessment of rheumatic disease monitoring. The PAINAD has been validated for pain assessment and response to pain management but has the risk of being overly sensitive to psychology stress, often very apparent in people with dementia. Both the PAINAD and Abbey Pain Score tools rely on observation by another of the patient’s vocalisation and facial and body expressions and movements e.g. grimacing or guarding. Frustration can also manifest in facial expression changes which could be overly viewed as pain. These are likely to be seen more in advanced dementia, but we are more likely in years to come to have patients attending our outpatient clinics who have at least moderate dementia and are still living at home with support from partners or family. Do we go off what they say? Our assessment criteria don’t formally consider this in rheumatology so again it lacks validity. As for other criteria, inflammatory markers are often not raised in spondyloarthritic conditions so although they could be a helpful monitoring tool, inflammatory markers in reality often aren’t. An MRI scan to review evidence of active inflammation as a monitoring tool could work, but is this a dementia friendly investigation? Not always, as it is unfamiliar and difficult for some with more advanced impairment to comprehend a need to remain still in a confined space for 45 minutes or more. Is this also an appropriate use of a more expensive and potential anxiety inducing method, ethically or economically? So, it would appear there is no clear answer in how best to monitor a patient's response to treatments other than your own clinical judgement and application, where possible, of the Bath indices questions, perhaps with some alternative wording to simplify, prompting with body charts or signalling to describe pain presentation on a person's own body. The use of pain assessment tools may be beneficial too in order to holistically assess a patient; and a bit of a judgement call. The British Pain Society acknowledge pain assessment of people who lack cognition or suffer with dementia needs to be further assessed and tools further validated and reviewed in real life settings. As the population ages, and dementia and Alzheimer’s disease become set to peek at one million by 2025, and potentially 2 million by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Society 2014), do we need to reassess how we disease monitor in axial spondylarthritis?

Clare

References: Booth MJ, Kobayashi LC, Janevic MR, Clauw D, Piette JD. No increased risk of Alzheimer's disease among people with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: findings from a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. older adults. BMC Rheumatol. 2021 Nov 12;5(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s41927-021-00219-x. PMID: 34763722; PMCID: PMC8588609.Jang HD, Park JS, Kim DW, Han K, Shin BJ, et al. (2019) Relationship between dementia and ankylosing spondylitis: A nationwide, population-based, retrospective longitudinal cohort study. PLOS ONE 14(1): e0210335. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210335Jordan A, Hughes J, Pakresi M, Hepburn S, O'Brien JT. The utility of PAINAD in assessing pain in a UK population with severe dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011 Feb;26(2):118-26. PMID: 20652872. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2489Lichtner, V., Dowding, D., Esterhuizen, P. et al. Pain assessment for people with dementia: a systematic review of systematic reviews of pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr 14, 138 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-138Newman, A.B., Fitzpatrick, A.L., Lopez, O., Jackson, S., Lyketsos, C., Jagust, W., Ives, D., DeKosky, S.T. and Kuller, L.H. (2005), Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease Incidence in Relationship to Cardiovascular Disease in the Cardiovascular Health Study Cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53: 1101-1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53360.xOwnby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 May;63(5):530-8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530. PMID: 16651510; PMCID: PMC3530614. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis - PubMed (nih.gov)Royal College of Physicians 2007 A concise guide to good practice, A series of evidence-based guidelines for clinical management Number 8 ‘The assessment of pain in older people National Guidelines’ untitled (britishpainsociety.org)Schofield, P 2018 ‘The Assessment of Pain in Older People: UK National Guidelines’, Age and Ageing, Volume 47, Issue suppl_1, March 2018, Pages i1–i22, https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx192Vitturi, B., Suriano, E., Pereira de Sousa, A., & Torigoe, D. (2020). Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 47(2), 219-225. doi:10.1017/cjn.2020.14Cognitive Impairment in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis | Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences | Cambridge Core

Benefits - a podcastHannah Chambers is joined by Gemma Williams and Sue Hambidge, colleagues working as Occupational Therapists, to talk about welfare and what that means for those living with long-term conditions. This podcast will consider services that can support people, covering a number of areas of welfare including financial support. This is a topic for us as AHPs that can be difficult to know where to start, and it can certainly be stressful for those living with long-term conditions to be applying for these resources. Sue and Gemma will briefly run through the support available that all should aware of…[12 minute listen]

Hannah The Art of Physiotherapy: Clinical Reasoning & Decision Making by Dr Marie Therese McDonald, Physiotherapy Lecturer- a personal reflection and blog September 2021: Physiotherapy is a scientific profession where physiotherapists utilise evidence-based thinking, relying on our knowledge of disease and chronic illness, of anatomy & physiology, and of biomechanics. However, there is not just one logical sequence of steps or rigid structure to assess the people who seek help from a physiotherapist. After an assessment, there isn’t one path to follow in choosing and delivering treatments; there isn’t a magic formula for choosing the parameters of techniques, and/or treatments. I believe that in addition to science there is a form of art to physiotherapy, to tailor assessment and treatment, to customise a plan to suit a particular individual, to guide individuals on choosing the best option, to communicate with empathy and compassion while above all, to make actions objective, righteous and ethical.I am not the first person to believe that physiotherapy or medicine can be a form of art. The Hippocratic Oath, reads “In purity and according to divine law will I carry out my life and my art,” and, “So long as I maintain this oath faithfully and without corruption, may it be granted to me to partake of life fully and the practice of my art”. The Hippocratic oath, has been a feature of medical study and practice for hundreds of years, and refers to the practice of physicians as a form of art.

Since then we have established that assessment and treatment is not a straightforward process; this got me thinking about the processes that we make decisions through a process of clinical reasoning. Clinical reasoning is taught in the undergraduate curriculum from day 1, and every physiotherapist in clinical practice uses this process, but what exactly is it? and how do physiotherapists use it to make their decisions? So, first what is clinical reasoning? Well, there isn’t just one definition...here are a few... 'Clinical reasoning is the process by which the clinician interprets subjective information along with physical examination findings, in order to identify the most appropriate management decisions for individual patients' (Petty & Ryder 2017)'Clinical reasoning is the thinking and decision-making processes used in clinical practice that enable therapists to take the best-judged action for individual patients e.g. making a diagnosis, determining management plans and selecting strategies to establish collaborative interactions with patients' (Edwards et al, 2004)'Clinical reasoning is the means to wise action' (Cervero, 1988 cited in Hengeveld & Banks 2014)The one thing that these three definitions have in common is that by using clinical reasoning a physiotherapist must make ‘good decisions’ (wise action 1st quote, most appropriate management 2nd quote, and best judged action 3rd quote). What are our clinical reasoning and decision making processes to take logical steps to make the ‘wise decision’ of assessment and treatment? One model which has been suggested to aid the clinical reasoning process is a biopsychosocial model presented by Edward & Jones in 1995 (see figure below), they suggest clinical reasoning as a collaborative process between the physiotherapist and patient. The physiotherapists reasoning begins with initial concept, possibly from referral or cues from initial informal discussion and observation, where the physiotherapist starts with multiple hypothesis. The physiotherapist then refines these initial hypotheses collaboratively with the patient through the subject and objective examination, with their own knowledge, cognition and metacognition and the patients understanding of their problem that they are presenting with. This aids decision making in diagnosis and management.

Ref: Edwards and Jones (1996) in Jones and Rivett (2004)

This hypothetico-deductive reasoning model is common in physiotherapy practice, but is not the only model, and often physiotherapists won’t stick to one model. As an experienced rheumatology physiotherapist I often reflected that if you really listened to the person (patient), (top right within this model) they always told you what was wrong with them, or the thing that they really wanted help with. Often the initial cues that I received, possibly an altered gait, or change in movement pattern, was long-standing and not what the person in front of me was seeking help for, so my first reflection is that an initial hypothesis frequently could be wrong and taking time to listen to the person in front of you was the most valuable part of the assessment. My second reflection, is within my knowledge base. Physiotherapy is a very rich profession with very knowledgeable and compassionate people. As my knowledge base widened I did not just have hypothesis A, B & C, I had also experience of A-Z, and while I could deduce that hypothesis B, M & X were the most likely ones I often could not discount the unusual presentation of a previous patient. Effectively, the more I knew, the less certain I became. Discussions with colleagues (mostly with a cup of tea) were always helpful to me. As an anxious practitioner, I never wanted to miss anything or get something wrong, but as time went on I realised I often didn’t have definite answers, but once I had considered and discounted red flags I could continue to define then refine my hypotheses. When working in rheumatology with people with long term chronic conditions, we really got to know our patients and their journey. From a humanistic point of view, health emphasises the whole individual rather than the focus of certain parts such as a shoulder problem, or a flare of the arthritis. From my point of view, although the clinical reasoning model is useful and part of my practice, I needed to consider the value of the interactions between physiotherapist and person, to consider the compassion and empathy that we show individuals that seek help and share their story with us (which might not be easy for them). I have been very privileged to work and learn from compassionate members of the MDT. I have been told that often patients valued the interactions and the therapeutic ability to share their story, to be listened to and understood, more than a treatment or strategy that was offered. Therefore, to conclude, as physiotherapists our knowledge of science is our base, with clinical reasoning and clinical reasoning models integral within our practice. The variation that clinical reasoning allows in our thought processes and decision making forms part of the ‘art’ of physiotherapy. In addition, listening allows us to focus on the whole person in front of us – what is important to them, and place value on the quality of our interaction, so we can deliver care with empathy and compassion. There really are many skills to being a physiotherapist, and I’m sure many more which I haven’t touched on.

Marie Therese

References Clinical Reasoning for Manual Therapists (2004). Publisher: Edinburgh, United Kingdom: Elsevier, Butterworth-Heinemann. Editors: Jones M.A., Rivett D.AIan Edwards, Mark Jones, Judi Carr, Annette Braunack-Mayer, Gail M Jensen, Clinical Reasoning Strategies in Physical Therapy, Physical Therapy, Volume 84, Issue 4, 1 April 2004, Pages 312–330, https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/84.4.312Management of musculoskeletal disorders (2014). Publisher: Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone / Elsevier. Authors: Kevin Banks, Elly Hengeveld, Matthew Newton, G.D. Maitland.Musculoskeletal Examination and Assessment - 5th Edition, A Handbook for Therapists (2017). Publisher: Elsevier. Editors: Nicola Petty, Dionne Ryder

Women and Axial Spondyloarthritis: The Way Forward

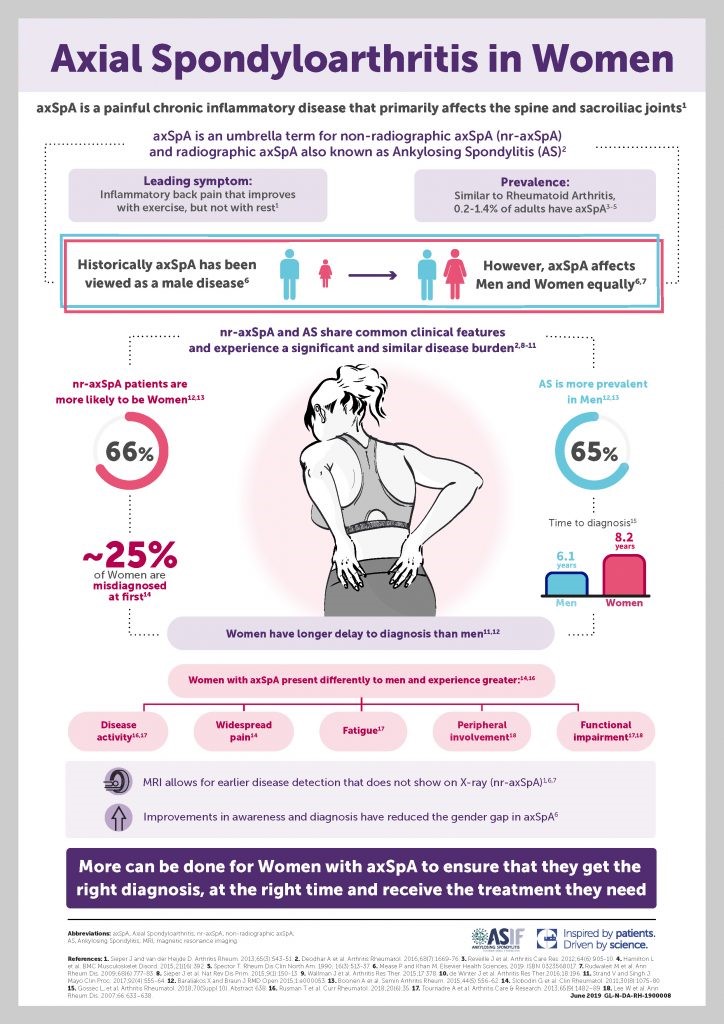

When I began working in Rheumatology, I predominantly worked with groups of men, aged over 40, and having a diagnosis of Ankylosing Spondylitis. Over nearly a decade of working in the field, I have seen an immense shift in the demographic of axial spondyloarthritis patients. In recent years I have worked with more mixed gender groups, some women-only groups, ranging from 18-80 years of age. This likely reflects our expanding knowledge and diagnostic capabilities, and to a large degree, the use of MRI to demonstrate early or discrete inflammatory changes in the spine and sacroiliac joints, indicative of what is now termed, axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA).

In recent years attention has turned to the disease path of women with axial SpA and how this can differ from men with the same condition. Below is a summary of some of these findings and an explanation of our role as therapists in improving outcomes for female patients. Delay in diagnosis The umbrella term of axial spondyloarthritis, includes both ankylosing spondylitis (or radiographic axial SpA), where changes to the spine and pelvis are seen on x-ray and non-radiographic axSpA where inflammatory changes are seen only on specific MRI sequences. Generally, equal numbers of men and women are diagnosed with non-radiographic axSpA but men are more likely to develop progressive bone growth and therefore ankylosing spondylitis. The presence of more readily detectable changes on imaging may help explain way the current average delay in diagnosis is around 8.2 years for women vs 6.1 for men (ASIF, 2020). X-ray is a cheaper and more readily used form of imaging in primary care, whereas the use of MRI sequence confirm axSpA is often only applied where the clinician will already have some degree of suspicion. The disparity in diagnosis may also be due to a less classic, “barn-door” presentation of axSpA among women; they tend to have more peripheral symptoms (enthesitis, dactylitis) and widespread pain* perhaps mimicking other conditions if not viewed in wider context. However, even the women I have met with very classic, axial-only symptoms, have often described how their early symptoms were explained (either by themselves or by clinicians) as being related to pregnancy or childbirth. The literature suggests women tend to have more extra articular manifestations (EAMS) such as; anterior uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. The presence of EAMS could be key clues to aid diagnosis if recognised by a health professional with knowledge of the signs and symptoms of axSpA. The National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society (NASS) have recently launched their Gold Standard Time to Diagnosis programme; https://nass.co.uk/get-involved/gold-standard , aiming to reduce the delay in diagnosis from 8 years to just 1 year. Educating health professionals to recognise the diverse presentation of axSpA, particularly in it’s early stages and in women will be key to achieving this. Disease Burden Evidence suggests the subjective burden of axSpA is higher in women than men. A 2020 review of the literature surrounding gender differences in AxSpA by Wright et al. describes higher self-reported functional loss, higher fatigue, more pain and lower quality of life among women with axSpA compared to men. From the research I have co-authored around sleep in axSpA, we also found sleep to be poorer in women and associated with higher levels of anxiety and depression (Wadeley et al., 2018). So perhaps the impact of AxSpA may be greater in women or, at least, they are more likely to tell us so. We must be cautious not to interpret this as women over-reporting symptoms; it may be a case that men with axSpA are less likely to tell us just how much they are suffering and access the help they need. Pregnancy and Childbirth Women with axSpA have higher levels of pre-term births and caesarean section (Hamroun et al., 2020) with no increase in miscarriage or still births. There is also suggestion that active disease is a predictor for pre-term delivery (Zbinden et al., 2018) As therapists we may play a key role in modifying disease activity through appropriate exercise prescription and advice on pain, fatigue and sleep management. Having worked in obstetrics, I can see the areas of overlap but also key differences in exercises prescribed in pregnancy and for axSpA. Modifications to stretching regimes may be needed but also particular attention to rib expansion exercises and maintaining general activity and function. Advice on sleeping positions, relaxation techniques and pacing can be helpful for all women in pregnancy. Hydrotherapy can be a great way for pregnant women to maintain mobility in the later stages of pregnancy and can help with pain relief. Sadly, many women will not be able to access a pool at the moment due to covid precautions. Pelvic floor dysfunction Watching an excellent webinar by Elaine Miller (@GussieGrips) as part of the Therapies Live event in May, I was struck by how prevalent continence problems are among women in the general population. Pelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction can be closely linked and given that sacroiliac pain is a key feature of axSpA, it may follow that there is a higher prevalence of pelvic floor dysfunction among women with AxSpA. To my knowledge, female continence issues in axSpA have not been formerly researched or explored (please correct me if I have missed any studies) but a higher level of sexual dysfunction has been reported in women with AS (Sariyildiz et al., 2013). I would therefore encourage therapists to have a conversation with their female (and male) patients around continence and sexual dysfunction and seek advice/refer on to their pelvic health colleagues. This is not comfortable ground for us MSK/ rheum physios but given that continence problems can be a real barrier to exercise and physical activity, it should be a key part of our treatment plan. www.gussetgripper is a great resource for patients and therapists and a good lesson in working outside your comfort-zone!

Emily

References: Hamroun S. et al. FR10305 Fertility and pregnancy outcomes in women with spondyloarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2020. Annals of Rheumatic Diseases, conference abstract and poster presentation. 79:S1 Sariyildiz M A, et al. The impact of anklylosing spondylitis in female sexual functions. International Journal of Impotence Research. 2013. 25:104-108 Wadeley et al. Sleep in ankylosing spondylitits and non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: associations with disease activity, gender and mood. Clinical Rheumatology. 2018. 37(4):1045-1052 Wright G et al. Understanding differences between men and women with axial spondyloarthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2020. 50: 687-694 Zbinden A et al. Risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes in axial spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: disease activity matters. Rheumatology 2018.57(7):1235-1242 Infographic: www.asif.info

|